A Revolting Development

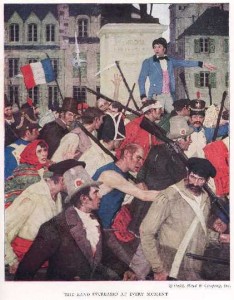

June 5 has come, and Paris does indeed rise up, with insurgents taking control of a third of the city by the end of the day. Gavroche has a great time playing at war as he runs off to join the unrest, and even Enjolras and his followers are exhilarated at this stage.

At last, the day of the barricade – or rather barricades – arrives, and Victor Hugo spends a great deal of time discussing the difference between an insurrection and a mere revolt. A lot of it retreads the opening section of part four which established the political climate in 1832, but he makes his philosophical points a bit clearer here: an insurrection moves society forward (or tries to). “Insurrection is a thing of the spirit, revolt is a thing of the stomach.” He considers revolution to be a valid form of societal change, then compares historical revolts to state which ones were justified and which were not.

At last, the day of the barricade – or rather barricades – arrives, and Victor Hugo spends a great deal of time discussing the difference between an insurrection and a mere revolt. A lot of it retreads the opening section of part four which established the political climate in 1832, but he makes his philosophical points a bit clearer here: an insurrection moves society forward (or tries to). “Insurrection is a thing of the spirit, revolt is a thing of the stomach.” He considers revolution to be a valid form of societal change, then compares historical revolts to state which ones were justified and which were not.

Some interesting observations: Any revolt that fails “strengthens the government it fails to overthrow.” Hugo really disapproves of political philosophy that analyses only effects and not causes (he applies the term “moderate” here, or rather the translator does, which I imagine is a case of changing terminology). The battle of students vs. soldiers was a battle of age: Young men ready to die for their ideals vs. older men ready to die for their families.

He naively believes that giving everyone the vote will prevent future insurrections.

“The riots threw a garish but splendid light on what is most particular to the character of Paris” – Yes, Paris has the best riots, too.

Rather than trying to show the whole insurrection of June 5-6, 1832, he explains that he’s chosen just one incident, “certainly the least known,” so that he can show us a detailed picture.

Funeral Spark

One of the things that bothered me when watching the recent movie was the way the students essentially hijacked General Lamarque’s funeral. At the time I figured it was a moviemaking choice to be more dramatic. It turns out it was another case of returning to the book. Speeches were made, the hearse was dragged around, and people actually started shooting.

Barricades were apparently very popular. One quarter had 27 spring up within an hour. Rioters “recruited” the populace, requisitioned weapons (sometimes leaving receipts!) seized garrison-posts, and held a third of Paris! The ABC group isn’t a tiny revolution – they’re a tiny part of a bigger one.

Meanwhile, outside the rebellious districts, it’s business as usual.

Some odd occurrences amid Parisian uprisings: “in 1831, the firing stopped to allow a wedding to pass.” In 1839, an old man with a beverage cart went back and forth between lines, selling drinks to both sides. In this particular insurrection, Victor Hugo himself (excuse me, “the marveling author of these lines”) walked out of a calm street into a war zone and was pinned behind a pillar for half an hour.

We’re off to Build a Barricade!

Gavroche is having a blast as he wanders around town, singing (“with the voice of Nature and the voice of Paris”), playing pranks, insulting passers-by, waving a broken gun that he’s found, shouting revolutionary slogans…and then helping a national guardsman to his feet when he falls from his horse. At one point he’s bitterly disappointed that he doesn’t have any money to buy one last apple-puff before his next adventure. Gavroche has got his priorities, after all!

He’s lost track of his brothers since that one night, though he offered to put them up again if they came back. He’s wondered about them, but (as mentioned previously regarding Valjean’s sister and her family) disappearances are common enough that he hasn’t put too much thought into it.

Scanning error: A veteran is reciting his wounds, “nothing to speak of,” and goes into a long list, in the middle of which is a bullet “in the left thing.” It’s supposed to say “thigh,” but it reminds me of one of Liam Neeson’s lines in Kingdom of Heaven.

Gavroche just sort of happens to run into Enjolras’ group by accident. They’ve got a rag-tag collection of weapons, and Feuilly is shouting “Long live Poland!” Bahorel wins Gavroche’s admiration by tearing down a public notice about eggs and Lent.

The group also picks up two old men who catch the eyes of the leaders: M. Mabeuf, whom Courfeyrac recognizes as Marius’ friend, and a bold, vigorous man whom no one recognizes as Javert (because Gavroche isn’t paying attention).

Courfeyrac realizes that they’re walking past his house, so he pops in to grab his wallet and his hat. A good thing too (maybe), because he runs into someone who’s looking for Marius. He thinks the boy looks like a little like a girl dressed as a boy, but hey, if he was a girl, he wouldn’t be dressed as a boy, right? I’m reminded of the Hob Gadling story in Sandman: World’s End, and his comment about seeing what you’re actually seeing instead of what you expect to see.

There’s a sort of casual exuberance about it all. Some of it is because we’re seeing it from Gavroche’s point of view, but it’s also in the early, intoxicating stage where they’re being driven entirely by idealism, before the harshness of war sets in. Next up: Building the barricade.

Pages covered: 883-914. Image by Mead Schaeffer from an unidentified edition of Les Misérables, via the Pont-au-Change illustration gallery. I don’t know if I’m going to make my goal of finishing commentary by the end of the year, but I’ve already got three more sections later on mostly written.